A Life devoted to Ethiopian Art: The Stanislaw Chojnacki Photographic Database

A Life devoted to Ethiopian Art

The Stanislaw Chojnacki Photographic Database

(Jacopo Gnisci)

Introduction

In March 2018 the Hiob Ludolf Centre for Ethiopian Studies (HLCES) at the University of Hamburg partnered with the Vatican Apostolic Library (BAV) to digitize and catalogue the photograph collection of Stanislaw Chojnacki which was bequathed by him to the Library. This paternership came about thanks to the initiatiative of Dr Delio Vania Proverbio, scriptor Orientalis at the BAV, and Dr Alessandro Bausi, Director of the HLCES. The project has been sponsored by the Beta maṣāḥǝft: Manuscripts of Ethiopia and Eritrea project and by the BAV. Dr Jacopo Gnisci was appointed as its principal cataloguer. Whereas, Dr Paola Manoni and Dr Irmgard Schuler (BAV), together with Dr Pietro Liuzzo (HLCES), were responsible for its technical aspects.

Stanislaw Chojnacki

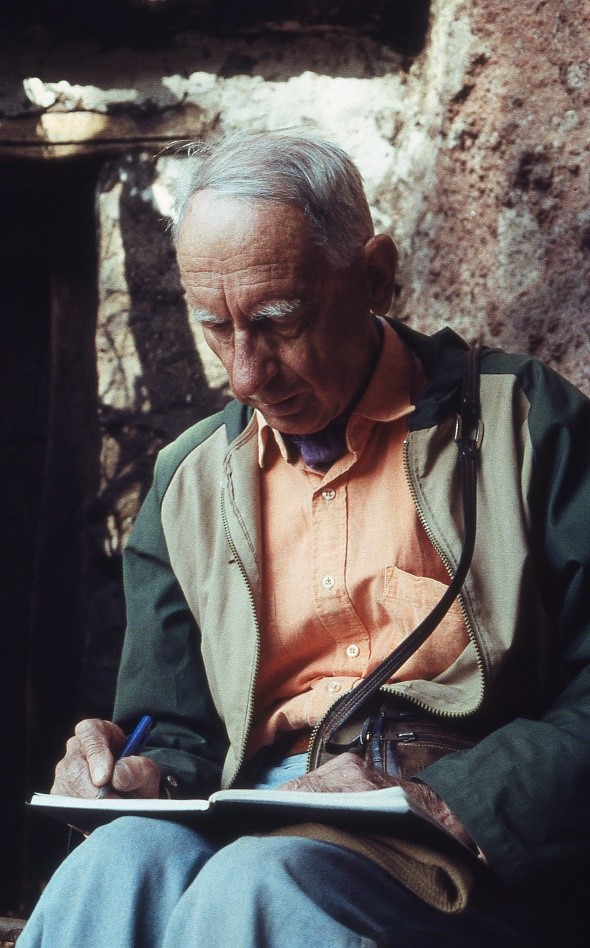

Stanislaw Chojnacki – born in Riga, Latvia, on 1 October 1915 – devoted much of his life to the study of Ethiopian art history until his death, in Sudbury, Ontario, Canada, on 3 July 2010. His interest in the artistic heritage of Ethiopia began soon after he accepted a position as Librarian at the University College in Addis Ababa in the early 1950s. An initial interest in the local contemporary art scene soon developed into a broader pattern of research on the artistic heritage of Ethiopia. Chojnacki played a key role in the opening of a museum at the Institute of Ethiopian Studies (IES), of which he became the first curator, and published extensively on Ethiopian art, taking into consideration a range of artistic media including icons, wall paintings, crosses, and church architecture.

S. Chojnacki taking notes in the church of Gannata Māryām in 2000 (© BAV)

Over the course of his many years of activity Chojnacki gathered a large amount of photographic evidence which he arranged meticulously in a series of folders. Already in the 1960s – in the wake of the discovery of the Garima Gospels (Leroy 1960) – he had recognized the importance of travelling across Ethiopia to document and catalogue the works preserved in the many ecclesiastical institutions scattered throughout the country (Chojnacki 1964). He continued to work on Ethiopian art until his death in 2010, focusing principally on Christian iconography (Chojnacki 1973a, 1973b, 1976b, 1976a, 1993), and on the icons and crosses used by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church (Chojnacki 1977, 1999, 2006).

The Collection

The extensive collection of personalia and photographic data that Chojnacki bequeathed to the BAV reflects his long, eclectic, and wide-ranging interests in Ethiopia. The collection includes photographs taken by Chojnacki during a period between the 1970s and the early 2000s, as well as material obtained from other sources including colleagues and Western repositories. Most of the images are of icons, paraphernalia (including crosses, censers, ewers, patens, and other liturgical equipment), wall paintings, churches, and illustrated manuscripts. Plants, landscapes, scenes of secular and religious life in Ethiopia, as well as the work of contemporary Ethiopian artists are also documented.

Cataloguing Principles and Practice

Chojnacki’s photographs are gathered in a series of 94 folders. The folders contained prevalently 35mm slides with the images framed in plastic or carboard mounts. Information about the exposure number and date in which the slide was developed appears in print on most, but not all, of the frames. Chojnacki generally used a pen to write a sequential number on each frame as well as details about the location in which each photograph was taken. At times, the slide frame or punched sheets inserted between the slide holders contain additional information, added by Chojnacki, about: the type of object depicted in the photo and its date; or the author of the photo. However, there are instances when it is not possible to determine when or where a photo was taken. There are also instances in which some slides are missing. In such cases, one occasionally finds a strip of paper in the empty holder with information about the location of the missing slides, which were often sent to a publisher.

The folders are loosely divided by regions (e.g. Lasta, Tigray, etc.) and each folder is subdivided into sites – mostly churches – visited by the author. The slides in each folder are generally not ordered chronologically. Thus one finds shots from different years of the same site mixed together. The same site may also appear in multiple folders. Icons and crosses are the objects that Chojnacki photographed in most detail, whereas one finds generally a selection of images of wall paintings and manuscripts.

The heterogeneous character of the photograph collection affected the criteria for selecting and cataloguing the images. It was also necessary to strike a balance between the time constrictions of the project, the large volume of material, the cataloguing rules of the BAV, and the necessity to ensure the accessibility and retrievability of the material through the metadata. In general terms, the cataloguing of the photographs reflects their arrangement in the folders. The photos in each catalogue have been sequentially grouped in clusters of one or more images. Images were clustered together when they featured the same principal object.

Each cluster of images has a specific shelf mark, such as Chojnacki.28(1-12).[See https://digi.vatlib.it/view/STP_Chojnacki.28(1-12), accessed on 23/11/2018] The first number is in sequence and is specific to the group of photos, while the numbers in parenthesis indicate the total number of images in that cluster. The images were acquired following the order of the folders. Thus the same object will have more than one shelf mark if photos of it are found in more than one folder. Where present, and when it was possible to identify this information, the digital card for each shelf mark contains the following varying information:

- Author

- Title

- Production

- Original Version Note

When the author was identified as someone else from Chojnacki, the images will not be available for consultation online. Title indicates the main object depicted in the photograph (e.g. cross, church, icon, etc.) and the location in which the photo was taken (e.g. Maḫdara Māryām, Mitāq ʾAmanuʾel). The names used for the locations are those found in the Beta maṣāḥǝft application. Production corresponds to the date in which the photographs were developed. A date range indicates that the images were developed, and therefore taken, on multiple occasions (e.g. 1994–1997), a question mark indicates that it was not possible to establish when some or all of the images were developed.

Original version note contains information about the type of object depicted in the photograph and details about its location, date, and medium. In some cases there is also a brief description of the item. For manuscripts, when such identification was possible, the title of the principal text is given and, if known, the EMML project number. In the case of objects featuring figurative imagery, a brief description of the main themes is also provided. In a small number of cases this information is provided by Chojnacki. In most cases is was supplied by the principal cataloguer, Jacopo Gnisci. Due to time limitations, only the main object depicted in each cluster of photographs has been described, but further data may be added in the future since the photographs may contain secondary objects of interest. The date ranges are generally wide, since relative dating methods were mostly employed in the cataloguing process. When multiple objects can be seen at the centre of the photograph, the date range is typically wider, since it takes into consideration the approximate date of the oldest and newest item in that shot.

The transparencies were digitized following the guidelines and principles of the library’s digitization workflow (Manoni 2013; Manoni, Núñez Gaitán and Schuler 2018), refined and adapted to meet the needs of the project. The cataloguer acquired the slides as uncompressed TIFFs using an Epson Perfection V600 Photo scanner with a resolution of 2400 dpi. Some of the transparencies were scratched or covered in dust. Even after the dust was removed manually, particles sometimes appeared in the digital image making it necessary, at time and when possible, to restore the images using a graphics editor. Slides were not acquired when they:

- Were too out of focus or poorly taken to be of value

- Were duplicates of acquired slides

- Featured content that could not be classified or identified

Once acquired, the digitized images were renamed using ReNamer and converted into the Flexible Image Transport System (FITS) format for storage. They were stored on the BAV’s IT systems using the web-based management software Inside and catalogued using the library’s V-smart integrated system.

Finally, historical and geographical information about the places in which the photographs were taken was supplied or updated in the Beta maṣāḥǝft application following the specific TEI guidelines of the project (Reule 2018; Liuzzo, Reule et al. 2018). Each repository on the app has a specific XML ID that was embedded in the metadata of the Vatican through V-smart to enable the interconnection of data between the catalogues.

Consultation

It is possible to view and download (as small- or medium-sized JPEGs) the photos that have been already catalogued at: https://digi.vatlib.it/stp/Chojnacki. All the images are supplied with a watermark. Using the online catalogue of the BAV it will be possible to search Chojnacki’s photographic database on the basis of the metadata described above, that is to say, by date, object, and location. Furthermore, by using the Beta maṣāḥǝft application, it is also possible to find the objects by location. The application also provides additional information about the history and geographical position of the repository that is not available on the Vatican’s catalogue.

Conclusion

The Stanislaw Chojnacki photographic database will provide scholars specializing in a range of disciplines with access to a large corpus of photographic data on which to work. Its value lies in the fact that many works documented by Chojnacki remain unpublished or are kept in locations that can only be accessed with considerable difficulty. Furthermore, the cataloguing process itself will supply new information about the documented works (Bausi 2007; Gnisci 2017). The project thus fosters our knowledge about the artistic heritage of Ethiopia and Eritrea while promoting further research on the subject and, most relevantly, ensuring that the legacy of Stanislaw Chojnacki is preserved and made available for future generations of researchers.

Selected Bibliography

Bausi, Alessandro. 2007. “La catalogazione come base della ricerca. Il caso dell’Etiopia.” In Zenit e Nadir II. I manoscritti dell’area del Mediterraneo: la catalogazione come base della ricerca. Atti del Seminario internazionale. Montepulciano, 6-8 luglio 2007, edited by Benedetta Cenni, Chiara Maria Francesca Lalli, and Leonardo Magionami, 87–108. Montepulciano: Thesan & Turan.

Chojnacki, Stanislaw. 1964. “Short Introduction to Ethiopian Traditional Painting.” Journal of Ethiopian Studies 2 (2): 1–11.

———. 1973a. “The Iconography of Saint George in Ethiopia: Part I.” Journal of Ethiopian Studies 11 (1): 57–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/41988567.

———. 1973b. “The Iconography of St. George in Ethiopia: Part II: St. George The Dragon-Killer.” Journal of Ethiopian Studies 11 (2): 51–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/41988258.

———. 1976a. “A Note on the Baptism of Christ in Ethiopian Art.” Annali Dell’Istituto Orientale Di Napoli 36: 103–115.

———. 1976b. “The Four Living Creatures of the Apocalypse and the Imagery of the Ascension in Ethiopia.” Bulletin de La Société d’archéologie Copte 23: 159–181.

———. 1977. “Two Ethiopian Icons.” African Arts 10 (4): 44–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/3335143.

———. 1993. “The Theme of the Bitter Water in Ethiopian Painting.” In Aspects of Ethiopian Art from Ancient Axum to the 20th Century, edited by Paul Henze, 53–67. London: The Jed Press.

———. 1999. “The Discovery of a 15th-Century Painting and the Brancaleon Enigma.” Rassegna Di Studi Etiopici 43: 15–42. https://doi.org/10.2307/41299976.

———. 2006. Ethiopian Crosses: A Cultural History and Chronology. Milan: Skira.

Gnisci, Jacopo . 2017. “Towards a Comparative Framework for Research on the Long Cycle in Ethiopic Gospels: Some Preliminary Observations.” Aethiopica 20: 70–105.

Leroy, Jules. 1960. “L’évangéliaire éthiopien du couvent d’Abba Garima et ses attaches avec l’ancien art chrétien de Syrie.” Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 104 (1): 200–204.

Liuzzo, Pietro, Reule, Dorothea et al. 2018. Beta Maṣāḥǝft Guidelines. Retrieved November 27, 2018, from http://betamasaheft.eu/Guidelines/.

Manoni, Paola. 2013. “Metadata Framework and Application Profiles in the Global Structure of Catalogs and Digitization Projects of the Vatican Library.” JLIS.It 4 (1): 425–34.

Manoni, Paola, Núñez Gaitán, Ángela and Schuler, Irmgard. 2018. The Vatican Apostolic Library’s Digital Preservation Project. Paper presented at: IFLA WLIC 2018 – Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia – Transform Libraries, Transform Societies in Session 160 - Preservation and Conservation with Information Technology, 1–13.

Reule, Dorothea. 2018. “Beta Maṣāḥǝft: Manuscripts of Ethiopia and Eritrea.” Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies Bulletin 4 (1): 13–28.

Acknowledgments

In addition to the persons listed above, the project could not have been carried out without the assistance of: Daniele Lisci, Corrado Ambrosi, Silvia Giuseppini, Eugenia Sokolinski, and Maura Del Canuto.